Construction activity is incredibly intensive work — creating the built environment is inherently disruptive to the natural environment. Governments balance the needs of both by requiring contractors, property owners, and others involved in construction to mitigate the effect of building activity on the environment, including air, water, and animal and plant life.

Environmental laws provide the backbone for permitting and reporting requirements on construction projects, while a wide variety of state and municipal laws impose even stricter rules. Failure to follow local and federal environmental requirements can lead to significant financial penalties, civil action, and even criminal charges.

Learn more: Construction & The Law

7 key environmental laws in construction

In construction, environmental regulations generally focus on stormwater, waste disposal, hazardous waste handling, and air quality. On a federal level, most of the environmental laws and regulations that apply to construction companies fall under the purview of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), though other federal and state agencies are closely involved.

The rules can apply to any construction jobsite in the United States. Owners, developers, or contractors who violate them can be subject to significant financial penalties and even jail time.

These seven laws form the basis for most of the environmental laws that construction companies need to follow. For further reading, see the Federal Environmental Requirements for Construction.

1. Clean Water Act

The Clean Water Act (CWA) established guidelines for discharge of pollutants into water within the U.S. In general, these laws apply to both contractors on the jobsite and the owner of the completed building.

According to CWA Section 402, a construction site must have a permit from the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) if it is:

- On an acre or more of land

- A municipal, industrial, or commercial facility that discharges waste or stormwater directly from a point source into a lake, river, or ocean

NPDES permits are issued by states that have obtained EPA approval to issue permits or by EPA Regions in states without such approval.

EPA Flowchart: Do I need a NPDES permit?

2. National Environmental Policy Act

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires federal agencies to assess the environmental effects of their proposed actions prior to making decisions. As a result, this law generally applies to public construction, such as infrastructure projects. This law is administered by the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), an executive office of the President.

Under NEPA, federal construction projects typically require an Environmental Assessment, and may require an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS).

Under this law, federal agencies must assess the environmental effects of proposed projects prior to starting construction. An environmental assessment and an environmental impact statement may be required. These statements are usually prepared by the federal agency during the preconstruction phase. But contractors should be aware that a project may be delayed or interrupted if the proper assessments — and any required corrections — haven’t been made.

Some projects or specific types of construction work may qualify as a Categorical Exclusion (CATEX), meaning additional review is not required. An EIS may not be necessary if the assessment shows that the project has no significant impacts. Every federal agency has its own procedures for implementing NEPA requirements, including what qualifies as CATEX.

While the burden for NEPA compliance generally falls to the agency owner, contractors need to understand and follow the environmental requirements to both produce an accurate bid and reduce delays or penalties during construction.

3. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA)

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) is a federal law that governs the generation, transportation, treatment, storage, and disposal of hazardous waste. Hazardous waste includes common construction and demolition (C&D) waste like lead pipes, adhesives and coatings, solvents, asphalt waste, and many others.

The RCRA has three categories of generators:

- Large Quantity Generators (LQGs): contractors that generate 1,000 kgs (~2,200 lbs) of hazardous waste per month, or more than 1 kg (2.2 lb) of acutely hazardous waste per month

- Small Quantity Generators (SQGs): generate more than 100 kgs but less than 1,000 kgs of hazardous waste per month

- Conditionally Exempt Small Quantity Generators (CESQGs): generate 100 kgs or less of hazardous waste, and 1 kg or less of acutely hazardous waste, per month.

According to the EPA, most construction, demolition, and renovation companies are considered CESQGs. Construction material suppliers, especially those that produce or distribute solvents and other chemicals, may qualify as LQGs or SQGs. View pages 12-13 of RCRA in Focus: Construction, Demolition, and Renovation for a checklist of requirements for LQGs and SQGs.

Though contractors may be exempt from RCRA requirements, they still need to comply with state and local laws that apply to hazardous waste disposal and storage.

4. Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA)

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), also known as “Superfund,” covers improper disposal or intent to dispose of hazardous waste. View the list of chemicals subject to CERCLA here. The Superfund includes money to pay for cleanup when the parties responsible cannot be identified.

However, the EPA does have the authority — and responsibility — to determine liability for hazardous waste pollution and hold Potentially Responsible Parties (PRP) accountable.

Under 42 U.S.C. § 9607, there are four general categories of PRPs:

- Current owner or operator

- Past owner or operator

- Arranger

- Transporter

Contractors and engineers have been found liable under CERCLA in a variety of court cases. But don’t assume that this law only applies to those who dispose of hazardous waste on a jobsite. As the court found in Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp. v. Catellus Development Corp., a contractor can be liable even when they move contaminated soil to an uncontaminated area of the same jobsite.

A construction company that is considered a PRP will need to negotiate a settlement agreement with the EPA. Failure to comply with the agreement can result in daily penalties — up to $62,689 as of January 2022.

5. Endangered Species Act

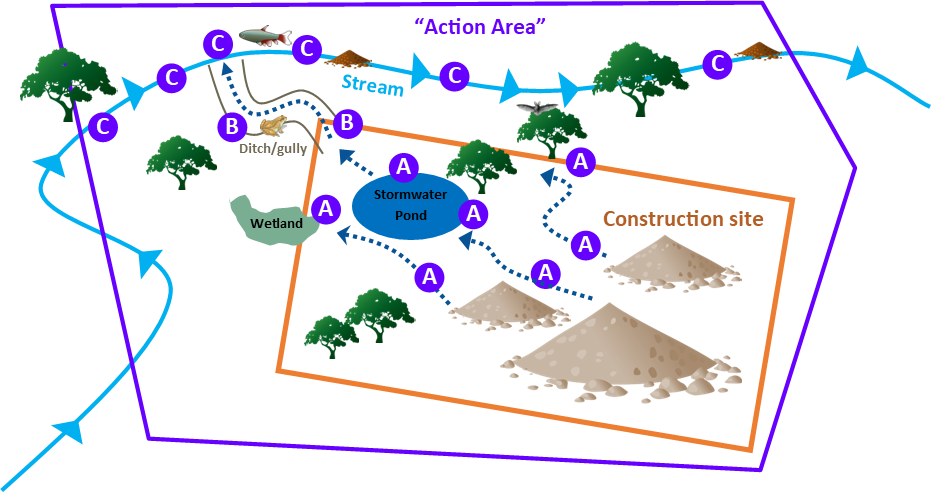

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) was created to protect endangered or threatened fish, wildlife, and plants, including their natural environment. In construction, ESA enforcement isn’t limited to the jobsite itself, but to the “Action Area” that is impacted by construction activity and stormwater runoff.

There are two federal agencies responsible for implementing ESA:

- US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)

- National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), also known as the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Service

A Permit for the Incidental Taking of Endangered and Threatened Species (also known as an “incidental take permit”) is required if construction activity will harm or harass a threatened or endangered species. View the ESA species list here.

FWS offers a variety of resources for contractors, engineers, and project owners, including an interactive map tool that allows users to identify potential impacts and review suggested conservation measures.

ESA violations can result in both criminal and civil penalties of up to $50,000 per violation and up to six months in jail.

6. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA)

The Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA) requires contractors to report on the storage, use, and release of hazardous substances (as defined by CERCLA).

The EPA has found that most construction sites are not subject to EPCRA planning requirements. However, certain jobsites may fall under EPCRA regulations. When this law applies, contractors and other operators must post material safety data sheets (MSDS) for the chemicals used, stored, or released on the jobsite.

Every state has its own commission, which is responsible for implementing EPCRA provisions within its state. They must report to the State Emergency Response Commissions (SERC) and/or the Local Emergency Planning Committees (LEPC) any releases of hazardous substances at the construction site if the amount released meets or exceeds the reportable quantity.

Non-compliance with EPCRA can result in penalties of up to $27,500 per day.

7. Clean Air Act (CAA)

The U.S. Clean Air Act (CAA) regulates air emissions from stationary and mobile sources. While most people are familiar with EPA’s enforcement of power plant or automotive emissions standards, the Clean Air Act also applies to construction activity, as well. While the EPA is responsible for enforcing CAA compliance, it can grant governing authority to the state.

Over the years, the EPA has tightened emissions standards for non-road engines, like those used in heavy construction equipment. These increasingly strict standards only apply to new equipment, with equipment manufacturers bearing the heaviest burden of compliance. The EPA also administers the Diesel Emissions Reduction Act, which funds retroactive emissions improvements on existing diesel engines through national and state programs.

The Clean Air Act also comes into play with the construction of power plants and other facilities requiring an air permit. Every state has its own permitting process and consequences for failure to comply. Contractors that begin construction work before the facility is properly permitted can be subject to penalties.

For example, according to the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, “Persons commencing work on such a project before obtaining the required permits, and any contractors engaged in such work, are subject to enforcement actions by the DEC.”

Enforcement actions include fines, civil and criminal penalties, and remedial orders to remove structures or materials from the jobsite.

One of the more common hazardous air pollutants in construction, asbestos, is also regulated under the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP). Prior to the demolition and renovation of buildings where asbestos is likely to be present, owners and/or contractors typically need to notify the appropriate authority (typically a state agency) before activity can occur. On projects where the amount of asbestos is over a certain threshold, contractors must follow specific asbestos control measures, and a trained monitor must be on site to observe the work.

Penalties for violating the Clean Air Act vary depending on the offense. In 2021, Alabama brought a lawsuit against a contractor for “unauthorized open burning of imported vegetation,” an alleged violation of the CAA that carried a penalty of up to $25,000 per day.

Top activities contractors need to plan for

Handling hazardous materials & toxic substances

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) gives the EPA the authority to control hazardous waste from the cradle to the grave. This includes waste generation, transportation, treatment, storage, and disposal. Amendments have added regulations to address underground petroleum tanks and hazardous waste storage. Under this law, the EPA may designate state entities to fulfill the requirements.

The EPA enforces two laws relating to the storage and handling of hazardous materials and toxic substances, including record-keeping and reporting rules for businesses. The Toxic Substances Control Act establishes reporting, record-keeping, and testing requirements for toxic materials. These include polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), asbestos, radon, and lead-based paint.

In addition, the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act requires construction companies (and other businesses) to report on the storage, use, and releases of hazardous substances to federal, state, and local governments.

Managing stormwater runoff

If your project will disturb one or more acres of land, you may need to get a Clean Water Act permit for the discharge of stormwater runoff from the site. Stormwater permits are issued either through the EPA’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) or a state’s permitting authority.

Getting a permit requires you to perform the following steps:

- Submit a notice of intent or permit application to your permitting authority. The notice or application requires you to certify that you will not harm federally listed endangered species.

- Develop and implement a stormwater pollution prevention plan (SWPPP). The plan must describe the physical characteristics of the site, list potential sources of pollutants, and identify the erosion prevention, sediment control, and stormwater management practices that will be implemented.

- If required by your permitting authority, submit a notice of termination when construction activities are complete or when someone else assumes control of the site.

Proper waste disposal

Traditional construction and demolition waste — like wood, roofing materials, insulation, plaster, or sheetrock — often ends up in landfills. However, the EPA regulates the kind of construction waste that is allowed to be disposed of in a landfill.

Contractors must follow specific disposal requirements for certain materials, including hazardous waste and other chemicals. The EPA also regulates the handling and disposal of building materials that contain lead and asbestos.

If contractors generate or handle hazardous wastes at the site, they must follow the regulations included in the RCRA. Potentially hazardous wastes include:

- Cleaners and solvents

- Paints (including lead-based)

- Paint thinners

- Asbestos

- Fluorescent lamps

- Storage tanks for petroleum products

Some states and municipalities have enacted statutes that ban the disposal of certain kinds of construction waste. For example, Vermont law (10 V.S.A. § 6605m) requires projects over a certain size to recycle leftover materials like plywood, clean wood, and scrap metal. Disposing of these items in a landfill can result in fines.

Mitigating air pollution

The Clean Air Act includes requirements for mobile and stationary sources of contamination. For construction projects, these may include heavy-duty vehicles and equipment and dust emissions from the site. The EPA continues to publish more stringent emission standards for diesel engines. Make sure that equipment and heavy-duty vehicles meet the latest requirements. Contractors must also maintain dust control and erosion control on sites that require it.

Improving energy efficiency

While they are primarily viewed as safety measures, local building codes can be used to promote energy efficiency and reduction of emissions. This can include insulation requirements, wall thickness, and energy efficiency of installed appliances.

These local codes generally meet or exceed the requirements of federal regulations. Through the permit and inspection process, they help ensure that construction meets local and national requirements.

The cost of environmental violations

Everyone on a project — including property owners, architects, and contractors — bears responsibility for ensuring that projects meet local, state, and federal requirements for environmental controls. While some contractors view environmental regulations as bureaucratic red tape, violating these regulations can lead to serious consequences.

EPA penalties vary based on the regulation, and reach nearly $75,000 per day for each violation:

- Clean Water Act: up to $54,833 per day, per violation

- Resource Conservation and Recovery Act: up to $74,552 per day, per violation

- Toxic Substances Control Act: up to $39,873 per day, per violation

- Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act: up to $57,317 per day, per violation

In addition to civil penalties, contractors can be subject to criminal penalties of up to $250,000 and 15 years in prison. And that’s not all: Beyond EPA fines and criminal liability, local and municipal governments have the authority to levy additional punishment for violations of ordinances or building codes, including revocation of a contractor license.