A payment bond is a type of surety bond purchased by a contractor to protect the property owner by guaranteeing payment to all the subcontractors and suppliers below them on the project.

There are so many different types of construction bonds used in the industry, it can feel overwhelming. The good news is that just two types of bonds that make up the majority of those used in the construction industry: payment bonds and performance bonds. General contractors are typically required to secure both performance and payment bonds on most federal and state projects, and they are sometimes used on private construction jobs as well.

But how do payment bonds work, and who do these bonds protect? Let’s dig in.

How do payment bonds work?

Payment bonds ensure that subcontractors and suppliers receive payment for the work they complete.

On a private construction project, if a subcontractor or supplier doesn’t receive payment, they can file a mechanics lien on the property. But when a payment bond is present, that bond effectively takes the place of the property for the purpose of making a non-payment claim. Instead, anyone who isn’t paid will need to file a claim with the surety, rather than securing their interest with the property itself.

This is why payment bonds are typically required on public projects, whether state or federal. The government doesn’t allow liens to be placed upon their own land. So to ensure that everyone on the job gets paid, they require the general contractor to purchase a payment bond.

You can think of a construction payment bond as an insurance policy in case the contractor cannot or will not pay the other parties on a construction project. The bond represents a “pile of money” that parties may make claims for payment against for payment of money they’ve earned on the project.

On public construction jobs (both at the federal and state level), the prime contractor (the one contracting directly with the public entity) is typically required to get a payment bond from an accredited surety company, and the bond itself must be a specific value.

Each state’s bonding requirement is different and varies upon a number of different factors, depending on the state’s Little Miller Act.

Federal or state project?

What you need to know about payment rights on federal construction projects

What you need to know about payment rights on state construction projects

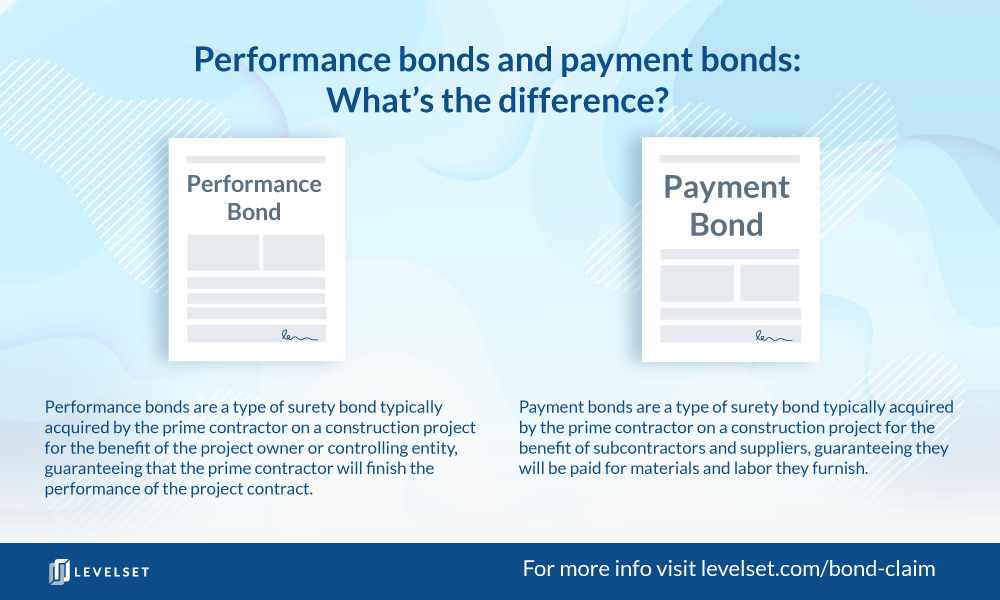

Payment bonds vs performance bonds: What’s the difference?

The difference between performance bonds and payment bonds is actually simple: A payment bond protects the property from lien claims by ensuring that subcontractors and suppliers get paid, while a performance bond guarantees that the contractor will complete the contract.

Payment bond requirements for all 50 states

Generally speaking, the required bond is set by the value of the project’s total contract value. However, in some cases, and for exceptionally large projects, it is not feasible to require the general contractor to obtain and post a many-multi-million-dollar bond. In these cases, there may be tiers of acceptable bond amounts as a percentage of the total contract, which decreases as the project value goes up.

For example, a construction payment bond may need to cover the entire construction contract amount for a $5 million project, but a $50 million project only requires a bond of 50% of the total contract value. The required bond amounts are set out in the specific statutes of the state in which the project takes place.

| State | Contract Amount | Required Bond |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | $50,000 | 50% |

| Alaska | $100,000 | Depends |

| Arizona | $100,000 | 100% |

| Arkansas | $20,000; charitable orgs $1,000 | 100% |

| California | $25,000 | 100% |

| Colorado | State: $100,000; City/County/Other: $50,000 | Depends |

| Connecticut | $100,000 | 100% |

| Delaware | All | 100% |

| Florida | $100,000, but projects less than $200,000 may be exempted from bond requirement by any gov’t agency; Orlando-Orange County Expressway Authority may waive bond reqs on projects less than $500,000. | 100% |

| Georgia | $100,000; $50,000 for DOT projects | 100% |

| Hawaii | $25,000 | 100% |

| Idaho | None given | 85% |

| Illinois | State: $50,000; political subdivision: $5,000 | 100% |

| Indiana | $200,000 | 100% |

| Iowa | $25,000 | Depends |

| Kansas | $100,000; $1,000 for state highway projects | 100% |

| Kentucky | $25,000 | 100% |

| Louisiana | $150,000 | 50% (in most cases) |

| Maine | $125,000 | 100% |

| Maryland | $100,000; None given on state highways | 50% |

| Massachusetts | Commonwealth: $5,000; All others: $2,000 | 50% |

| Michigan | $50,000 | Set by state, but no less than 25% |

| Minnesota | $75,000 | 100% |

| Mississippi | $25,000 but security may be required on contracts under that amount | 100% |

| Missouri | $25,000 | 100% |

| Montana | $50,000; school district projects: $7,500 | 100% – state; No less than 25% – municipal |

| Nebraska | State: $15,000; other: $10,000 | 100% |

| Nevada | $100,000 | 50% |

| New Hampshire | $35,000 | 100% |

| New Jersey | State Division of Building and Construction: $200,000; other state departments: $100,000 | 100% |

| New Mexico | $25,000 | 50-100% at state’s discretion |

| New York | None given | None given |

| North Carolina | $300,000 | 100% |

| North Dakota | All public work requires bond | 200% |

| Ohio | All public work requires bond | Not specified |

| Oklahoma | $25,000 | 100% |

| Oregon | $100,000; highway: $50,000 | 100% |

| Pennsylvania | $5,000 | 100% |

| Rhode Island | Roads: $50,000; all others: None given | 50-100% at state’s discretion |

| South Carolina | $100,000; DOT projects: $10,000 | Hwy – 50%, all other – 100% |

| South Dakota | State projects through Bureau of Admin: $50,000; others: $25,000 | 100% |

| Tennessee | $100,000 except highway are set by DOT | 25%; Hwy set by DOT |

| Texas | Municipality or joint board created under Transportation Code: $50,000; all others: $25,000 | 100% |

| Utah | All public work requires bond | 100% |

| Vermont | Not specified | 100% |

| Virginia | $500,000; $250,000 for Commonwealth- funded highway projects which may be increased to $350,000 in some cases | 100% |

| Washington | Up to $35,000 – 50% retainage may be substituted in place of bond; between $35,000-$100,000: individual sureties may be substituted for bond; otherwise: $100,000 | 100% |

| Washington DC | $100,000 | 50% |

| West Virginia | All public work requires a bond | 100% |

| Wisconsin | State: $100,000; local: $50,000 | 100% |

| Wyoming | $7,500 | 50% for contracts under $100,000 |

How filing a bond claim helps contractors get paid

When a project participant such as a subcontractor or material supplier has a payment issue on a project, filing a bond claim can be a very effective way to secure payment. Payment bonds give construction parties an option to get paid without the ultimate step of a foreclosure sale of the property. While litigation may still ensue, recovering from a pile of cash has no real difference than recovering through the property itself, and practically, it may be easier.

Make a bond claim now

Levelset takes all of the guesswork out of the claim process. We’ll verify your rights, research the project information, and ensure your claim is done right.

Further, a bond claim brings another party into the mix to help resolve issues: surety bond companies. These surety companies will apply extra pressure on the contractors to resolve issues. And since sureties will not continue to provide bonds to contractors with claims filed against them constantly, GCs pay special attention to bond claims that are filed against bonds they provide.

Payment bonds on private construction projects

The procedure for a private payment bond depends on the state you are in. Some states disallow mechanics liens to be filed if there is a bond posted on the project already. For example, in Florida, the state lien law prohibits unpaid contractors and suppliers from filing a mechanic’s lien if there is a bond posted. Instead, the unpaid parties must file the claim against the bond. Other states do not have specific laws on this procedure. Practically speaking, small private projects rarely have payment bonds, and these are reserved for large-scale commercial projects.

Bonding off a mechanics lien

In some cases, a private bond may be used as a reactionary tool to “bond off” or “bond around” a lien against a property. In other words, a bond is posted after the mechanics lien is filed to release the property but still make sure the lien claimant is provided security.

Payment bond claims yield results

Payment bond claims can be just as beneficial as mechanics liens and, in certain respects, can be even more effective. Payment bonds give construction parties an option to get paid without the ultimate step of a foreclosure sale of the property. While litigation may still ensue, recovering from a pile of cash has no real difference than recovering through the property itself, and practically, it may be easier.

Further, a bond claim brings another party into the mix to help resolve issues: surety companies. These surety companies will apply extra pressure on the contractors to resolve issues. And since sureties will not continue to provide bonds to contractors with claims filed against them constantly, GCs pay special attention to bond claims that are filed against bonds they provide.